Shapes and Games

Don't be a square

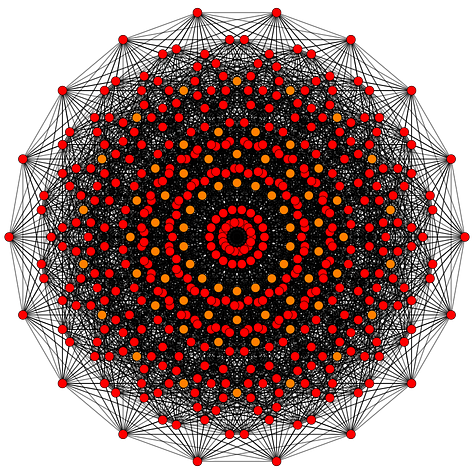

Years ago when my peers and myself prepared for university in the fall, I often heard of a pithy mental model passed around from student to student. Frequently referred to as the “College Triangle,” this concept comprises three elements: social life, adequate sleep, and good grades. This young adult adage unfortunately suggests that in university you will only be able to attain two out of the three needs. Recently, as work experience has moved itself from a “nice to have” to a “necessary but not sufficient” requirement for new graduates, students have been compelled to add work experience to create a square, a word often used as an insult for a person who is dull and unadventurous. As job security decreased over time and competition increases, a growing number of students shape their lives around this square, trading off the ink in their pen, once used to write a story of self exploration, for the relentless tracing of this two dimensional shape, boldening its rigid strokes. The shape originally used to describe tradeoffs has now cemented itself as a secular catechism. How will you live? Work, school, socialize, sleep.

In a month I’ll be returning for my final term of school, bracing myself for conversations that look like a modern art exhibition — think Piet Mondrian. Talks of anything hopelessly mutate into one’s concerns of full time employment, grades, and sanity. Ironically, the often unfiltered authenticity of the final topic is what keeps me sane. I don’t know what hurts me more, squares or the absence of shape altogether, pure hopeless nihilism.

“Don’t be a square.” In the time of need I like to listen to the wise words of Mia Wallace, a fictional movie character who proceeds to mistake heroin as cocaine and almost ODs a few hours after she says “Don’t be a square.” End of tangent.

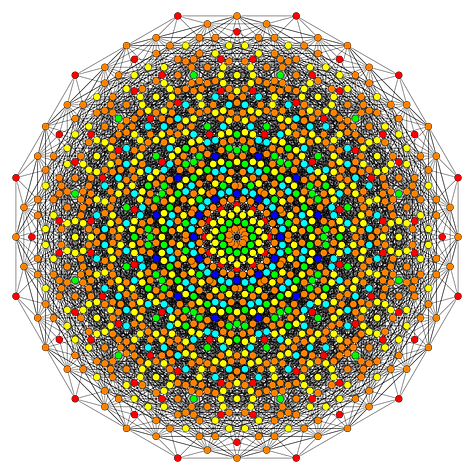

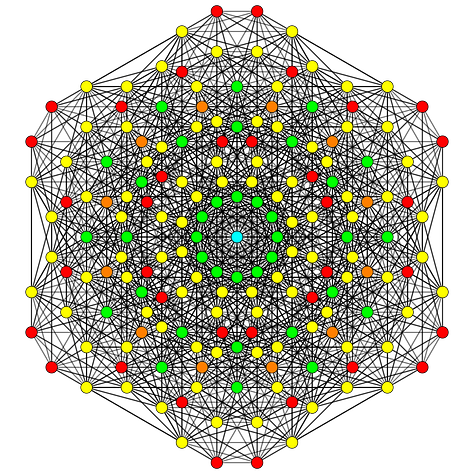

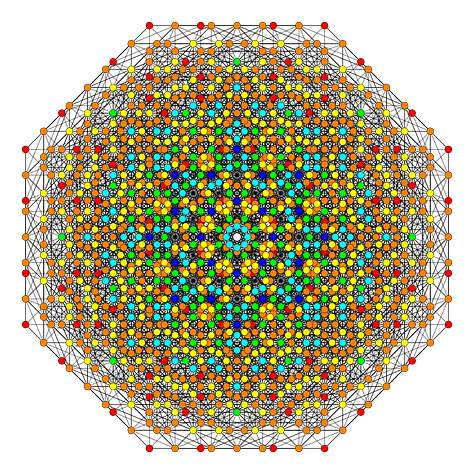

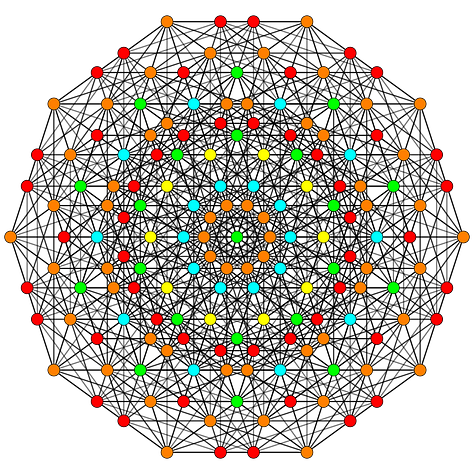

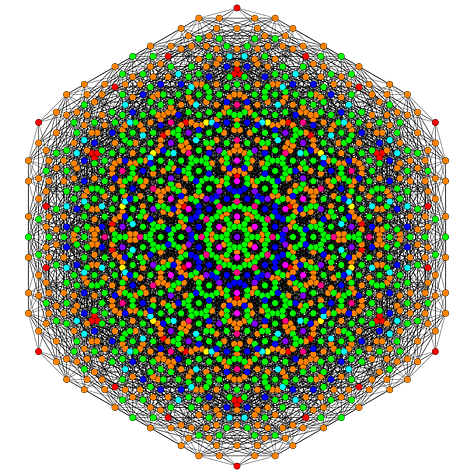

Optimistically, the early to mid twenties are also the periods where a person’s shape evolves, often fracturing from one imposed by an authoritative body (or a part of the body, say an invisible hand) and rebuilt with new undertakings, exploration, and exposures to new environments. Being in my twenties with several peers of similar ages give me the privilege to see several squares molded by one’s own hands into beautiful fractals, waves, and tapestries. In retrospect, it is fascinating to see how these evolve. From lines to polygons and finally polytopes of varying colours and textures, they often tell a story of childhood, dreams, trauma, interwoven with the signature threads of the cultural zeitgeist. The twenties are the years we learn our souls yearn for more than the requirements needed to be a productive citizen. Although necessary to most, it has been proven to be insufficient.

Each unique structure represents what we seek for in life. Similar to a game we build for ourselves, each sub-pattern represents a lifelong quests we set for ourselves. Like video games, some quests are audacious in nature — think slaying a dragon. Others can be unique to our idiosyncrasies, and of course there are always the small side quests. There are popular games like wealth, success, and love. There are games everyone plays but most leave on the bottom of the dusty shelf such as creating meaning. There are games you can finish, ones we face in specific segments in our lives then move on from, and Sisyphean games. What does a square indicate? It’s the barcode for the Triple A young adult exclusive, post graduation employment. Several have already used this analogy and described it well.

As patterns tend to behave, several of these games are universal archetypes embedded in literature, entertainment, and communication, causing a feedback echo between behaviour and media. This is of course a given, succinctly summarized by my friend Tony, “We live in a painful postmodernist world.” Tangentially, I find it amusing that it is as if a citadel, or more fittingly the largest GameStop, lies in Plato’s world of forms stocked with cartridges enough for eight billion souls at a time. Before I completely derails, whether postmodernist or platonist, we all connect and bond through the sharing of these ubiquitous patterns and games. It’s why although I didn’t sound like it, I do appreciate when peers speak of school and jobs. I’ll always value human connection over none.

Most analogies of games and quests, are fantastic and practical frameworks for parts of our life but they tend to have clear rules, patterns, win conditions, and feedback. Unfortunately life does not. I think it’s an expedient habit of ours to simplify the complicated in the pursuit of improving standalone metrics. Naval’s example of single player games paint a more accurate picture of life than others, but I fear many rationalize a multiplayer game to be a single player one. I learned rationality can ironically be used to deceive oneself as much as emotion can. I hope using both shapes and games to reflect on our lives can reduce the error and lead to more fulfilling lives.

So take a step back and look at the shape of your life. Is it beautiful?